Determining Limits of Flammability: Which ASTM Method E918 vs. E681?

TJ Frawley, Project Manager, Flammability Testing and Consulting Services, Fauske & Associates

When determining the flammability limits of your product for an SDS or to optimize your process while maintaining high safety standards, it can be somewhat confusing choosing the correct testing method. The two most requested methods are ASTM E918: Determining Limits of Flammability of Chemicals at Elevated Temperature and Pressure and ASTM E681: Concentration Limits of Flammability of Chemicals (Vapors and Gases).

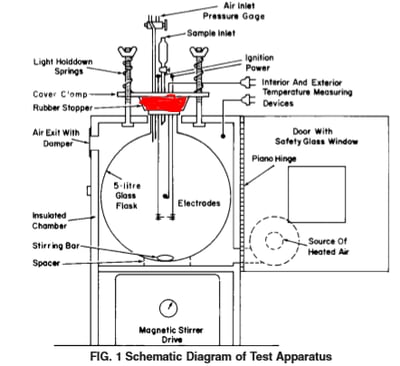

This piece will examine the differences between these two types of flammability tests and the advantages and obstacles of those differences. As a starting point, the most glaring difference between the two is that E918 is performed in a 5-Liter stainless steel vessel and E681 is performed in a 5-Liter glass flask that incorporates a rubber stopper to seal the vessel. It is important to remember this key difference as it is the basis which most greatly sets the two methods apart and can thus influence data interpretation.

The similarity of the methods are few but deserve mention. Both methods aim to determine the same outcome – boundaries of vapor/gas flammability. Both can be run at elevated temperatures, although E918 allows for a greater range; and E918 can also be run at above, or below, atmospheric pressures.

It is the opinion of the Flammability division here at Fauske and Associates that E918 is the better of the methods because of the increased accuracy, versatility, and safety, that testing in a stainless steel vessel can provide.

ASTM E918 has a greater accuracy because the resolution of an ignition is determined by an established percentage of pressure increase which is measured by calibrated pressure transducers. In the United States a 7.0% rise of absolute pressure constitutes an ignition. At the ambient pressure of 14.7 psia, the 7.0% rise is equal to an increase of 1 psia in pressure. Europeans use a 5.0% pressure rise criterion as the defining threshold of an ignition as is stated by the Swedish Standards Institute in SS-EN 1839.

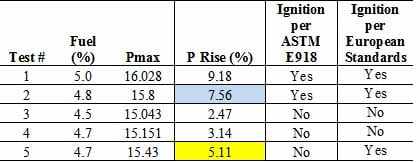

Below is a chart displaying a dataset of five tests determining the LFL of methane. The yellow highlighted cells illustrate a 5.11% pressure rise (Test #5). This would be considered an ignition in Europe, and the LFL of methane would be reported as 4.7% fuel (assuming testing of 4.6% resulted in non-ignitions). However, in the United States, Test #2 where a pressure rise of 7.56% occurred, would be considered an ignition, and 4.8% fuel would be reported as the LFL (blue highlighted cell).

The conception the 7.0% pressure rise and 5.0% pressure rise are not without controversy. The reasoning for those numbers being used as an ignition threshold are still debated today. However, there is consistency for every lab in the United States using a 7.0% pressure rise, and there is consistency across European labs that use a 5.0% ignition indicator. The end user of the LFL data needs to be aware of the exact method used for the determination.

While E918 has an objective, clear, and distinct definition of an ignition, E681 relies on subjective visual observations to make the distinction between an ignition and a non-ignition. The standard states in section 3.1.2, “propagation of flame – as used in this test method, [is] the upward and outward movement of the flame front from the ignition source to the vessel walls or at least to within 13 mm of the wall, which is determined by visual observation.” This creates bias when determining “what is and what isn’t an ignition.” What one person may interpret as an ignition, another person may disagree. Herein lies the uncertainty in the end results.

Below are two charts comparing the LFL results of methane obtained being using each standard. The top chart has data from ASTM E918, and the bottom chart was obtained from ASTM E681. Please note the difference of fuel percentage that correspond with the lowest ignition. Using ASTM E918 the reported LFL is 4.83%. The result using ASTM E681 in the glass flask is about 0.2% higher.

Lower Flammable Limit of Methane in a 5-L Stainless Steel Vessel

Lower Flammable Limit of Methane in a 5-L Glass Vessel

Correlation does not equal causation, therefore, the difference in results may not stem from the differences in the standards. However, based on the data in the top chart using a 7.0% rise as the threshold for an ignition, we can clearly distinguish an ignition from a non-ignition. The lower chart is more ambiguous.

Even when using video to record testing of E681, the outcome is not always as dependable in practice as the standard describes.

|

In this picture our ignition source is fired. It

Here a flame has been identified. However, it

|

|

The pictures above depict a typical test ran according to ASTM E681. While this test is more visually appealing than watching a line move on a graph, it can be difficult to view and interpret. These pictures were specifically chosen to illustrate the difficulty of determining an ignition visually. This is not an uncommon scenario.

Any material that may produce a residue or a solid product in decomposition, such as chemicals with a saline group or one that generates soot or tar, will decrease the technician’s visibility and impair their ability to distinguish between an ignition and a non-ignition.

E918 also has more versatility and can replicate more processes by being able to reach higher pressures and temperatures. Here at Fauske and Associates using E918 we have been able to perform testing above 300 psia. The other method cannot test at any pressures above ambient levels. According to E681, the 5-L glass flask is vacuum sealed with a rubber stopper.

On the top: a diagram of E681 setup with a rubber stopper sealing the glass flask

On the top: a diagram of E681 setup with a rubber stopper sealing the glass flask

On the bottom: a stainless steel 5-L vessel sealed with a stainless steel lid

If pressurized above ambient pressure, the rubber stopper will pop, and the test mixture will be compromised. Not only will this test have to be repeated, if the sample is hazardous, a safety concern now exists.

Finally from a safety perspective, testing in a completely sealed stainless steel vessel is overwhelmingly preferable to testing in a glass flask that relies on a vacuum sealed rubber stopper.

Stainless steel will not crack or shatter; glass might. Although engineers and technicians are trained and experienced at avoiding dangerous scenarios, the possibly remains. We are igniting chemicals that may result in high pressure explosions. It is not outside the realm of possibly for the glass flask to crack or break.

As previously mentioned, a steel vessel can be pressurized. This is also very important for purging the vessel after a test. Any hazardous decomposition products can be purged by pressurizing the vessel with nitrogen and then evacuated into a scrubbing system or into a fume hood. This cannot be done in a glass flask. As soon as the pressure inside the flask becomes

greater than the atmosphere outside the flask, the rubber stopper will break its seal with the glass flask and hazardous gases or vapors will be ejected from the flask in an uncontrolled manner into the surrounding environment. Therefore, the purging process must rely on vacuum purging alone, which most likely will increase the time to fully purge. This adds to the total

turnaround time of the test and an increase in cost.

There are benefits to E681. It is visually more appealing because a person can actually see reactions in the vessel. Also the equipment for E681 is less expensive and may be less expensive to perform testing.

It is always important to know the pros and cons when choosing a testing standard. For more information on flammability testing go to our flammability testing page which contains information on FAI's testing methods along with other flammability testing resources.