Post Tags

Shock, Explosion and Friction Hazards - Identification and Mitigation

Fauske & Associates

9 min read

By Richard Kwasny, Ph.D., CPEA, CSP Senior Engineering Consultant, Chemical Operations, Michael Lim, Mechanical Engineer & Zach Hachmeister, Director of Operation and Chemical Engineer, Fauske & Associates

Background

A material’s sensitivity to energetic forces in the form of shock and friction can result in an unwanted explosive event in various scenarios during transportation, storage, handling, and plant unit operations. Rotating equipment (i.e., pumps, hammer mills, micronization operations) can impart sufficient energy to initiate an explosion in highly sensitive materials. Rough stationary surfaces (i.e. pipes, filters, and other abrasive surfaces) can result in frictional forces that can also initiate the explosive decomposition of a friction sensitive material as it flows/accumulates on a rough surface. If a material has a low threshold for shock and/or friction sensitivity, then great care must be given to unit operations that have the potential to impose a sudden impact or abrasive force on the material. Therefore, it is important to both identify materials that are shock and/or friction sensitive and quantify how shock/friction sensitive the material is before proceeding with process or transportation operations.

Shock (Impact) and Explosion Hazard Identification

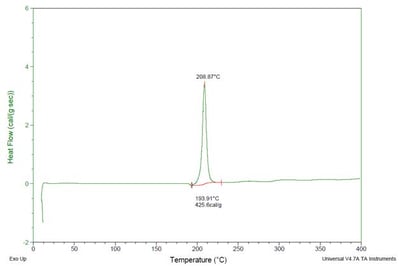

As a first step, a literature search and review of the material safety data sheet (MSDS/SDS) should be conducted for indications of explosive properties. Many materials with these adverse properties can be identified because they have highly energetic functional groups, i.e., Nitro (R/Ar-NO2), N-Oxides (R3N+—O-), metal azide M(N3), etc. A full listing of explosive groups can be found in various references (Bretherick’s Handbook of Reactive Chemical Hazards, Sax and Lewis, etc.). A useful screening test to estimate if a ma- terial has the potential to be shock and/ or funk sensitive is a differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) test. This test method evaluates the thermal behavior of a given sample between temperature ranges of 25°C – 400°C. Analysis of the data resulting from the DSC test can provide the onset temperature and heat of reaction. These parameters can then be inserted into Yoshida’s correlation to estimate both the shock sensitivity (SS) and explosion propagation (EP) of the material.

SS = log (Qdsc) -0.72 x log (Tdsc-25) - 0.98

EP = log (Qdsc) -0.38 x log(Tdsc-25) – 1.67

where Qdsc is the energy of the exotherm in calories g-1 and Tdsc is the onset temperature of the exotherm in °C. If the value for SS or EP is ≥ 0.00, then the material is predicated to be shock sensitive or demonstrate explosive propagating properties, respectively.

According to Yoshida’s correlation, this sample is predicted to be both shock sensitive and explosion propagating. It would be a prudent practice to conduct a BAM Fallhammer test to verify Yoshida’s prediction since this material is considered to be highly energetic.

Figure 1: DSC Test Data of an Energetic Material

When using this screening test, it is critical that there be no loss of mass during the DSC test – a small mass loss will result in a very high energy loss and misleading conclusions. The data shown above was obtained using a SWISSI M20 high-pressure crucible, shown in Figure 2, which are leak proof and can contain pressures of up to 3,500 psi.

Figure 2: High Pressure DSC Crucible Gold (SWISSI M20)

In cases where the DSC test indicates that the material is capable of releasing a signifi- cant amount of energy within a small temperature range, such as the plot in Figure 1, it is good practice to conduct further explosive testing. The most commonly used test method to identify and measure if a material is shock sensitive to impact is the BAM Fallhammer test. This test is used to measure the sensitivity of solids and liquids to drop-weight impact and to determine if the substance is too dangerous to transport or process in the form tested. The test apparatus is shown in Figure 3 to the right.

During the test, the sample is subjected to an energetic shock created by dropping a known mass from a known height. Upon impact, the sample is monitored for evidence of reaction, decomposition, or explosion. The actual energy imposed upon the sample is equal to the potential energy of the mass at the set height. The test results are assessed on the basis of whether an “explosion” occurs during any of up to six trials at a particular impact energy. The test result is recorded as the lowest impact energy at which at least one “explosion” occurs in six trials. The test result is considered “positive” if the lowest impact energy at which at least one “explosion” occurs in six trials is 2 J or less, thus classifying the substance as too dangerous for transport in the form in which it was tested. Otherwise, the result is considered “negative”. For industrial plant situations, every material with shock sensitive properties must be assessed on a case by case basis and the effect of impact forces from all sources must be considered (i.e., pumps, agitators, manual operations, grinding, milling, micronization, and other unit operations). However, for general batch operations, it is usually recognized that if a material’s sensitivity to impact energy is > 60 J, the material can usually be handled safely, provided a hazard assessment is conducted.

Friction Hazards

Currently, there is no correlation to predict friction sensitivity. If a material has highly energetic functional groups, displays unexplainable discoloration when subjected to handling, displays characteristics of being shock sensitive, or is highly exothermic, it is prudent to conduct a friction hazard evaluation.

Friction Test

The most common test method used to identify and measure the sensitivity of a substance to frictional stimuli is the BAM Friction test apparatus shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: BAM Friction Test Apparatus

This test method involves placing a sample between a fixed porcelain peg and a moving porcelain tile. The sample is then subjected to one friction cycle at varying forces from 360 N to six lower forces until an “explosion” or “no reaction” is observed.

Test criteria and method of assessing results are on the basis of:

• Whether an “explosion” occurs in any of up to six trials at a particular friction load, and

• The lowest friction load at which at least one “explosion” occurs in six trials.

The test result is considered “positive” if the lowest friction load at which one “explosion” occurs in six trials is less than 80 N; therefore, classifying the substance as too dangerous for transport in the form in which it was tested. Otherwise, the test result is considered “negative”. If the BAM Friction test yields a value > 360 Newton then it is generally accepted that the material will not ignite or decompose when subjected to frictional forces between two surfaces in a lab, plant, or in a transportation scenario.

Risk Mitigation/Transfer

Identifying a material as shock and/or friction sensitive is critical for safe-scale up and transportation purposes. Quantification of the level of the hazard is equally important. If the Fallhammer test result is < 60 J and the Friction test is < 360 N then a process hazard analysis can identify if the current procedures and safeguards are adequate. If they are not, then recommendations can be implemented to ensure the material can be handled safely. Working with a material possessing explosive properties in a facility not designed to handle explosives can be very challenging. However, there are at least two solutions to this problem. The first is to consider finding an alternative material with similar chemical properties but less shock/friction sensitivity. Such an example is given in Chemical & Engineering News where David am Ende et al substituted hazardous perchloric acid salt for a bis-tetrafluoroborate salt and were able to scale-up without incident. This was an excellent example of substituting a less hazardous material and making the process inherently more safe.

If the process chemistry cannot be redesigned using less shock/friction sensitive materials or intermediates, it is best to consider using a facility that specializes in handling explosive materials. There are a number of explosive manufacturers that have GMP facilities that are capable of handling the potentially highly hazardous stages of a process. Subsequent process steps can then be handled in-house, once the high risk step has been completed. There are many pharmaceutical companies that recognize this hazard, transfer the risk appropriately and resume processing at a safer stage.

If the finished material has explosive properties, then special excipients can be added to reduce shock/friction hazards. However, this must only be attempted by personnel with expertise in dealing with explosive materials. Explosive manufacturers have this type of expertise and are experienced at reformulating their products to allow for safe transport. For more information regarding this topic, please contact Zachary Hachmeister at Hachmeister@fauske.com or 630-887-5223 www.fauske.com.

References

• Estimation of Explosive Hazards of Self-Reactive Chemicals from Differential Scanning Calorimetery Data. Tadao Yoshida et al. Prediction of Fire and Explosive Hazards of Reactive Chemicals (Kogyo Kayaku), Vol. 48 No. 5, 1987.

• Perchloric Acid Salts, Dr. David am Ende et al, Chemical & Engineering News, March 6, 2000.

• Bretherick’s Handbook of Reactive Chemical Hazards, 6th edition, P. G. Urben, Butterworth Heinemann, 1999.

• Manual of Tests and Criteria Recommendations on the Transport of Dangerous Goods Model Regulations, 4th revised edition, United Nations, Sept. 1, 2005.

#hazards identification, #shock hazard, #transportation sensitive materials, #swissi crucible