Growing interest in hydrogen builds on the recognition that clean hydrogen can play a crucial role in global decarbonization. Currently 40% of all carbon dioxide emissions come from power plants burning fossil fuels to generate energy. Other relatively high pollution sectors include transportation and industrial factories. Consumption of hydrogen for energy produces only water, and hydrogen has a high energy density by mass, which makes it an interesting low carbon alternative. The demand for hydrogen has increased threefold since 1975 and is expected to continue this trajectory, with the demand for clean hydrogen anticipated to be a crucial component of Net Zero Emissions by 2050 Scenario (NZE) and with a potential demand of 150 to 500 million metric tonnes of hydrogen a year. To try and meet this demand, there is a global push for financial investment in clean hydrogen at scale in both commercial and industrial applications.

Where Does Hydrogen Come From?

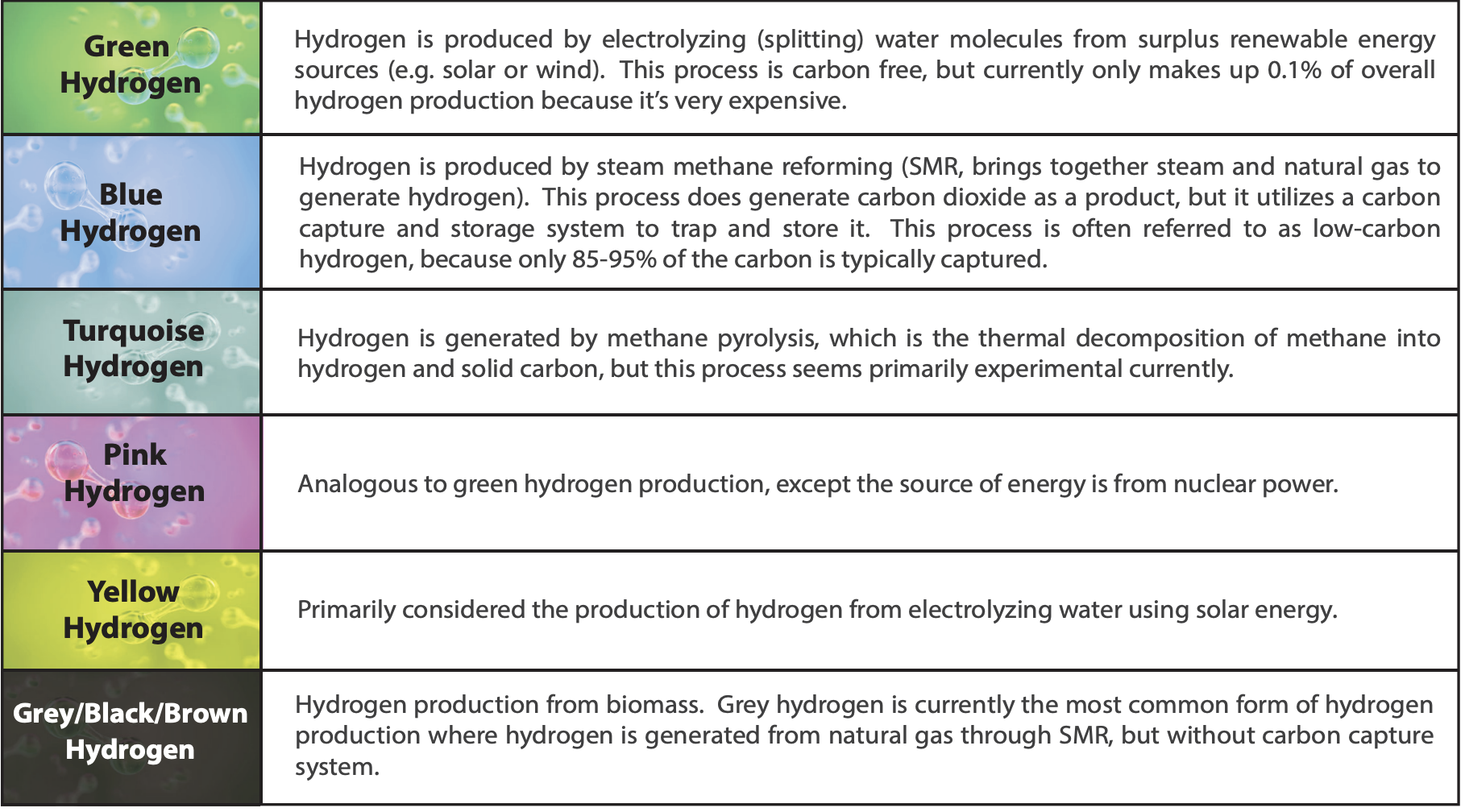

Not all hydrogen is considered “clean” as its production can sometimes be carbon intensive. Thus, while hydrogen is a colorless gas, it is typically described by color to represent its source. Green hydrogen is of particular interest to combat global warming, because it is produced in a “climate-neutral manner.” Table 1 provides a comparison of the commonly discussed hydrogen production methods.

Hydrogen Properties & Potential Hazards

Hydrogen has many properties that make it attractive as a source of energy, and many of which are inherently safe features, however there are potential hazards associated with any fuel source. Here are some of hydrogen’s properties, and how they might relate to potential hazards that must be considered depending on the application:

- Hydrogen is a colorless, odorless, and tasteless non-toxic gas typically in the form of a diatomic molecule (H2). While rare, hydrogen is a potential asphyxiation hazard in confined spaces. In addition to the gaseous form, hydrogen flames are also nearly colorless, and the low radiant heat and low emissivity of the flame can make early identification difficult.

- Hydrogen is non-corrosive; however, it can cause embrittlement leading to unexpected mechanical failures or leaks. Properly selected materials and system layout, periodic visual checks, adequate passive or active ventilation systems, and safety systems (e.g., leak or hydrogen detection sensors) are important aspects of a safe design.

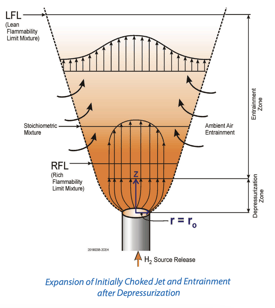

- Hydrogen has excellent energy density; however, its vapor density is very low (around 1/15th of air). This is great for the buoyant dissipation of a vapor cloud following a leak but can make it difficult to store large quantities of hydrogen. High pressure vessels can be used to store gaseous hydrogen; alternatively, hydrogen can be compressed, and stored under cryogenic conditions. Both options should be evaluated for potential overpressure hazards and unignited releases (e.g., loss of temperature control in cryogenic storage or fire exposure in gaseous storage, both of which can lead to rapid pressurization and a loss of containment).

- Hydrogen has a very large flammable range (typically considered 4% to 75% by volume in air) and a very high burning velocity when compared to other typical fuel types. This increases the likelihood and potential consequences of combustion (via fire or explosion). Despite hydrogen's propensity to diffuse quickly in air, high-pressure leaks can lead to unconfined jet fires or explosions, and the low minimum ignition energy of hydrogen makes it difficult to eliminate all potential ignition sources. Confined vapor cloud explosions (i.e., deflagrations or deflagrations that undergo transition to detonations, or DDT) are a hazard that must be considered and that can have potentially severe consequences. Proper siting and barriers can help to protect against this hazard and reduce the risk of a catastrophic event.

Hydrogen Safety

Developing a safe process to harvest or utilize hydrogen is much like developing any other safe process involving chemical hazards:

1. Identify Potential Hazards (via HAZOP, FMEA, or other tools)

2. Evaluate the Hazard Risk Level in Terms of Likelihood and Severity

3. Identify Preventative, Mitigative, or Elimination Techniques

4. Document the Findings, Employ the Techniques, and Train Personnel

5. Ensure Safety Systems and Facility Meet Relevant Regulations, Codes, and Standards

6. Periodically Review System and Monitor for Changes, and Repeat Process if Change Occurs

References:

https://www.iea.org/reports/the-future-of-hydrogen

https://www.iea.org/reports/hydrogen

https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/net-zero-coalition

https://www.energy.gov/articles/how-were-moving-net-zero-2050

https://netl.doe.gov/research/Coal/energy-systems/gasification/gasifipedia/hydrogen

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/07/clean-energy-green-hydrogen/

https://chfcc.org/hydrogen-fuel-cells/about-hydrogen/hydrogen-properties

https://www.energy.gov/eere/fuelcells/safe-use-hydrogen

https://www.nrdc.org/bio/christian-tae/hydrogen-safety-lets-clear-air

https://www.nrel.gov/hydrogen/safety-codes-standards.html