What is an Onset Temperature, and How Should I Use it to Better Understand My Reactive Hazards?

Onset temperature is the lowest temperature at which a chemical reaction is occurring at a measurable rate. Unlike certain flammability related quantities, chemical reactions are essentially always occurring, and there is still non-zero rate of reaction even at low temperatures where measurement is not possible. In other words, there is not a temperature “switch” that initiates a reaction. Therefore, the reported onset temperature is highly dependent on the instrument sensitivity, the procedure utilized for collecting the data (i.e. the time-temperature history of the material), the type of instrument (e.g. how adiabatic an instrument is), and the specific kinetics of the reaction. Therefore, caution must be employed when applying information on the measured reaction onset to a real chemical process.

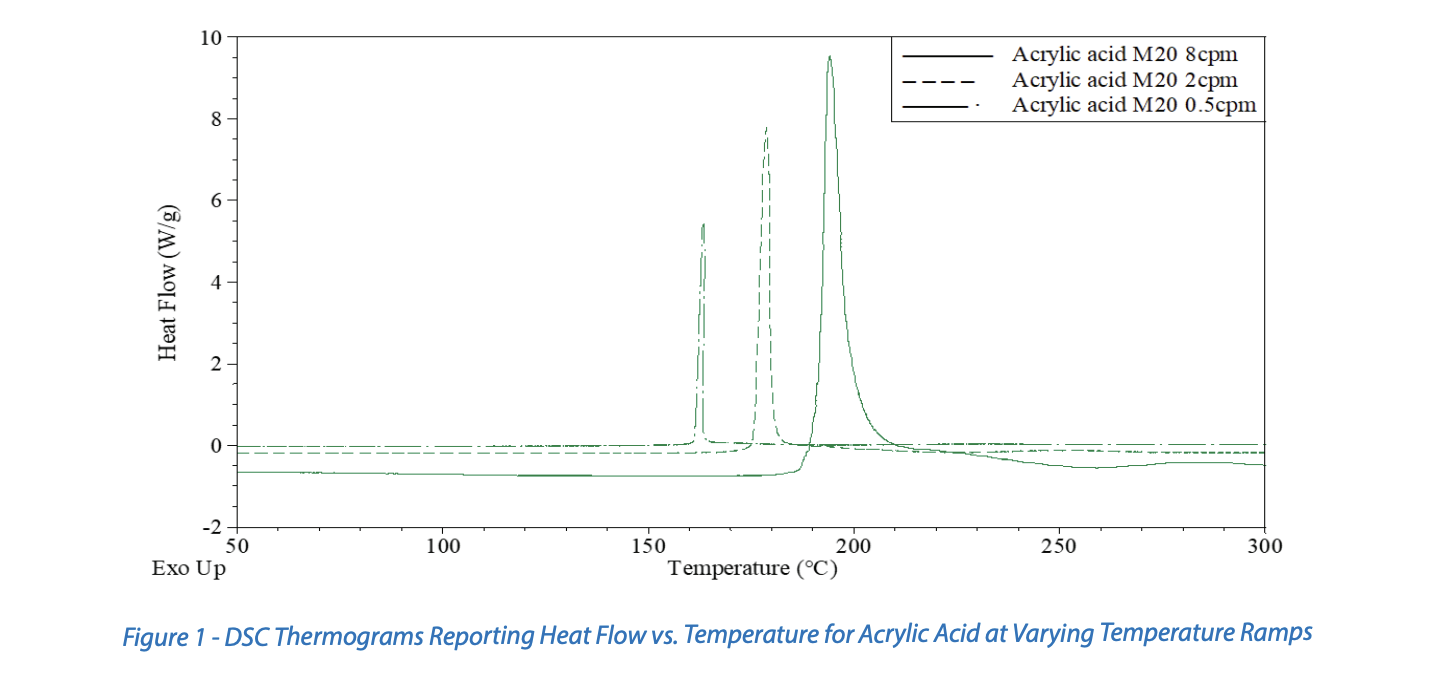

An example of the variation of observed onset temperature for various experimental procedures is shown in Figure 1. Presented are data from three Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) experiments conducted with varying heating rates. The DSC provides heat flow calorimetry data where the temperature of the material is controlled, and the resulting heat flow is measured. The observed onset temperature increases as the imposed heating rate increases, and this is expected in most cases. The experiment conducted with a 0.5°C/min imposed heating rate has an observed onset temperature around 160°C. The experiment conducted with an 8°C/min imposed heating rate has an observed onset temperature around 190°C. Differences in the observed temperature onsets depend on the kinetics of the reaction (e.g., reaction order, activation energy, autocatalytic behavior, etc.).

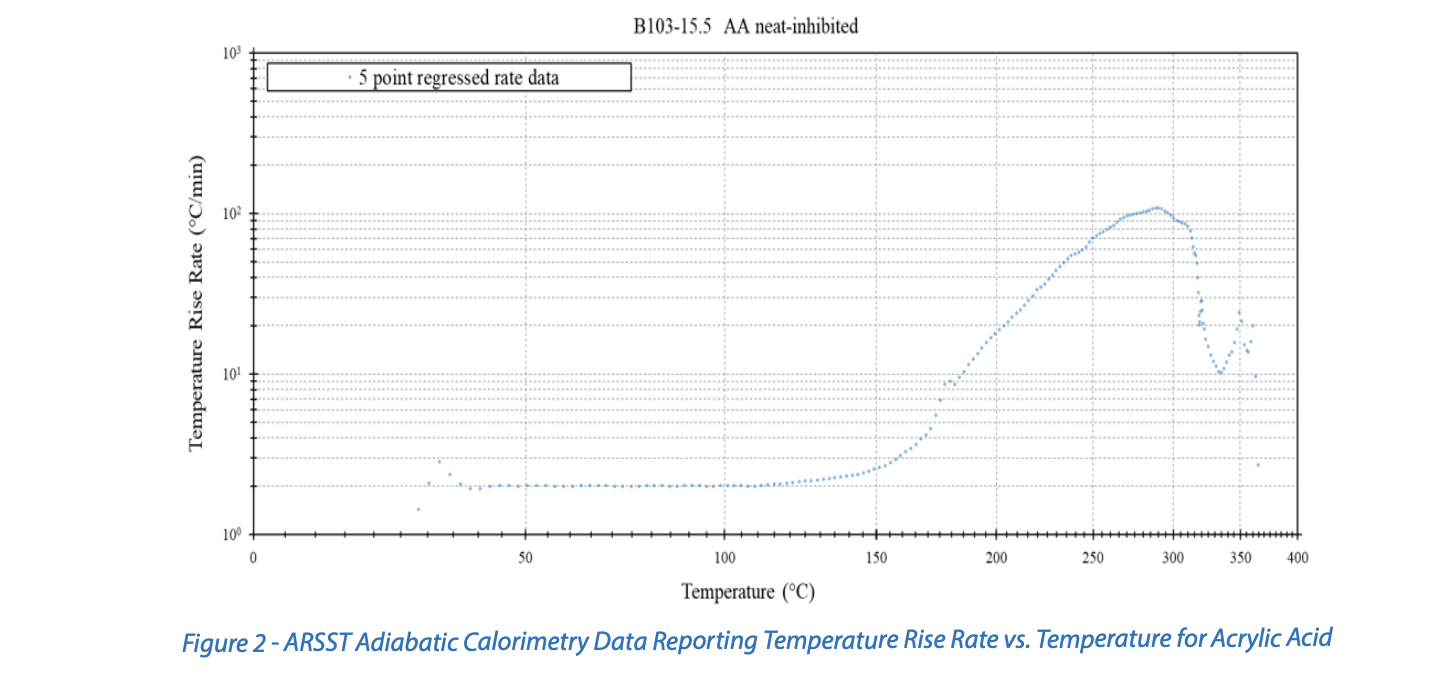

Figure 2 shows Advanced Reactive System Screening Tool (ARSST) adiabatic calorimetry data for acrylic acid. The ARSST is a low-phi adiabatic calorimetry instrument that typically operates with an imposed constant-power heating rate and in an open-system fashion where vaporization of the sample is suppressed by a superimposed inert gas backpressure. This experiment was conducted with approximately a 2°C/min effective heating rate. Here, the first deviation above the background heating rate is observable at approximately 120°C, which may be considered the observed onset in this experiment. This observed onset temperature is lower than what is depicted in Figure 1, illustrating the instrument and setup dependency on onset temperature.

It can be expected that when extrapolating this behavior to situations where materials are exposed to lower temperatures for longer periods of time (like ‘isothermal’ conditions that might be expected during storage or processing), the observed onset temperature will decrease. This can make it difficult to predict the behavior of large quantities of materials over longer periods of time. The “100 degree Rule” is a commonly assumed safety margin where 100°C below the observed DSC onset temperature is considered a safe processing temperature. As mentioned earlier, the variation in onset is dependent on a variety of things including reaction kinetics. It is therefore recommended to proceed with caution when applying this rule, unless prior experience on the kinetics of the specific reaction is available. In most cases, given enough time, and a large enough scale (which generally decreases heat losses), a reaction can reach completion at any temperature.

What isn’t described by onset temperature alone is the likelihood and consequence of a reaction occurring. More important than onset temperature for understanding a reactive hazard is the relationship between temperature and reaction time (e.g., how long will it take to reach peak reaction rates at a given temperature), as well as reactive rate of heat generation vs. rate of heat removal from the vessel/container at varying temperatures, time scales, and production scales. There are many ways to get the data necessary for understanding reactive hazards so they can be mitigated or prevented. The FAI team would be pleased to discuss your processes or concerns to help you develop a practical plan to evaluate the hazard and truly understand the risk.